Reinforcement Learning for 3D Molecular Design

By Robert Pinsler, Gregor N. C. SimmImagine we were able to design molecules with exactly the properties we care about. This would unlock huge potential for applications such as de novo drug design and materials discovery. Unfortunately, searching for particular chemical compounds is like trying to find the needle in a haystack: Polishchuk et al. (2013) estimate that there are between $10^{30}$ and $10^{60}$ feasible and potentially drug-like molecules, making exhaustive search hopeless. Worse yet, we don’t even know what the needle looks like.

In this blog post, we will outline how we combine ideas from reinforcement learning and quantum chemistry to catalyse the search for new molecules. We will explain how we can push the boundaries of the type of molecules we can build by representing the atoms directly in Cartesian coordinates. Finally, we will demonstrate how we can exploit symmetries of the design process to efficiently train a reinforcement learning agent for molecular design.

Re-framing Molecular Design using Reinforcement Learning and Quantum Chemistry

To be able to design general molecular structures, it is critical to choose the right representation. Most approaches rely on graph representations of molecules, where atoms and bonds are represented by nodes and edges, respectively. However, this is a strongly simplified model designed for the description of single organic molecules. It is unsuitable for encoding metals and molecular clusters as it lacks information about the relative position of atoms in 3D space. Further, geometric constraints on the molecule cannot be easily encoded in the design process. A more general representation closer to the physical system is one in which a molecule is described by its atoms’ positions in Cartesian coordinates. We therefore directly work in this space.

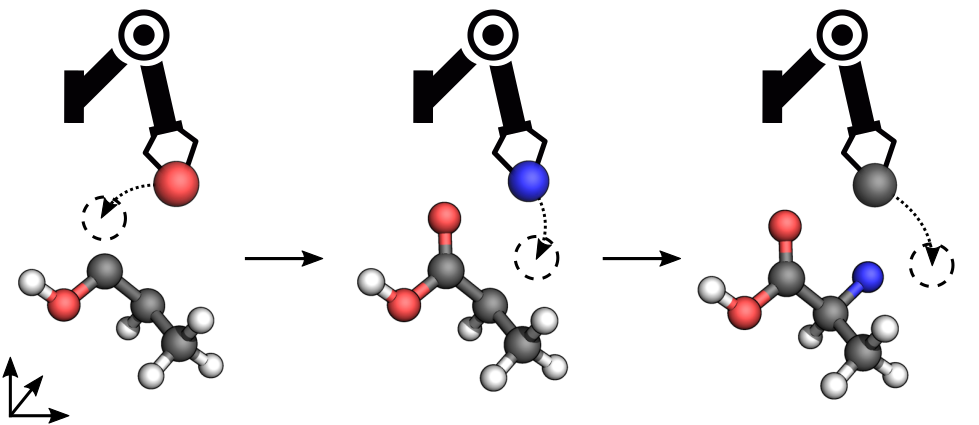

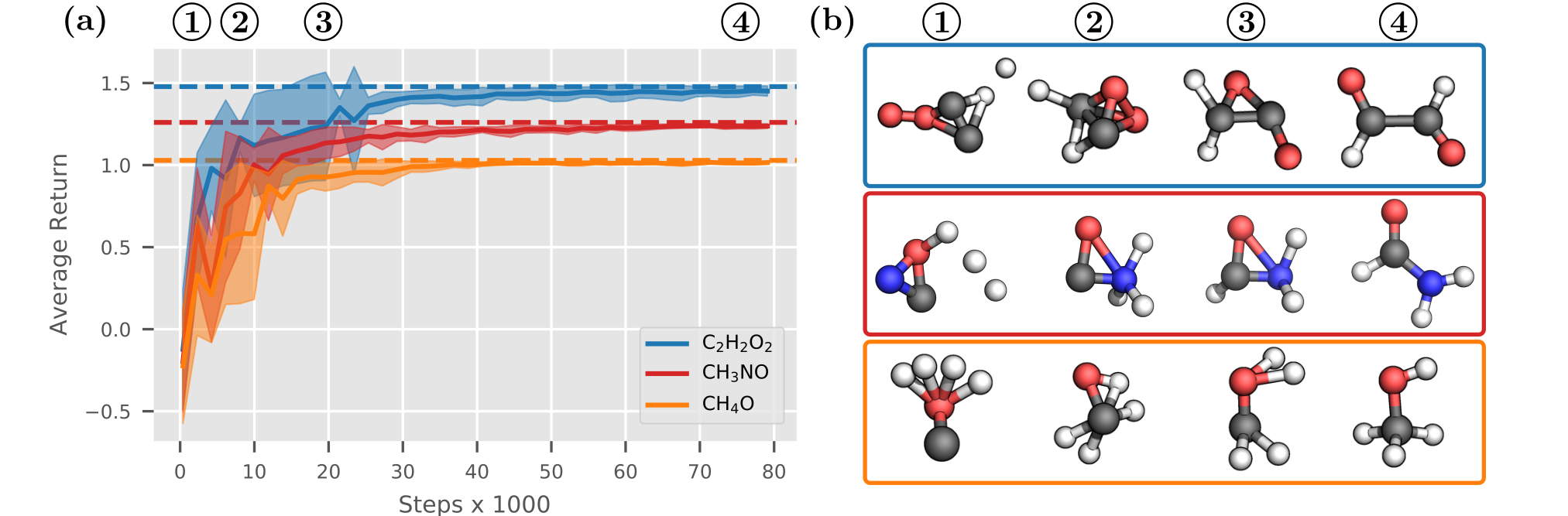

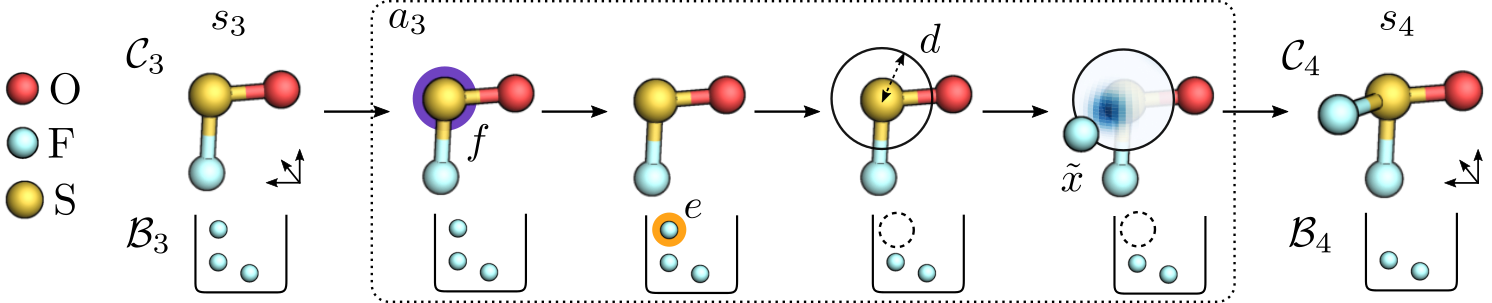

In particular, we design molecules by sequentially drawing atoms from a given bag and placing them onto a 3D canvas. The canvas $\mathcal{C}$ contains all atoms $(e, x)$ with element $e \in \{\ce{H}, \ce{C}, \ce{N}, \ce{O}\, \dots \}$ and position $x \in \mathbb{R}^3$ placed so far, whereas the bag $\mathcal{B}$ comprises atoms still to be placed. We formulate this task as a sequential decision-making problem in a Markov decision process, where the agent is rewarded for building stable molecules. At the beginning of each episode, the agent receives an initial state $s_0 = (\mathcal{C}_{0}, \mathcal{B}_0)$, e.g. $\mathcal{C}_0 = \emptyset$ and $\mathcal{B}_0 = \ce{SFO_4}$ (see Figure 1). At each timestep $t$, the agent draws an atom from the bag and places it onto the canvas through action $a_t$, yielding reward $r_t$ and transitioning the environment into state $s_{t+1}$. This process is repeated until the bag is empty.

Figure 1: We build a molecule by repeatedly taking atoms from bag $\mathcal{B}_0 = \ce{SOF_4}$ and placing them onto the 3D canvas. Bonds connecting atoms are only for illustration.

An advantage of designing molecules in Cartesian space is that we can evaluate states in terms of quantum-mechanical properties.1 Here, the reward function encourages the agent to design stable molecules as measured in terms of their energy; however, linear combinations of other desirable properties (like drug-likeliness or toxicity) would also be possible. We define the reward as the negative difference in energy between the resulting molecule described by $\mathcal{C}_{t+1}$ and the sum of energies of the current molecule $\mathcal{C}_t$ and a new atom of element $e_t$, \begin{equation} r(s_t, a_t) = \left[E(\mathcal{C}_t) + E(e_t)\right] - E(\mathcal{C}_{t+1}), \end{equation} where $E(e) := E({e, [0,0,0]^T })$. We compute the energy using a fast semi-empirical quantum-chemical method. Importantly, the episodic return for building a molecule does not depend on the order in which atoms are placed.

Exploiting Symmetry using Internal Coordinates (Simm et al., 2020)

Learning to place atoms in Cartesian coordinates requires that the agent exploits the symmetries of the molecular design process. Therefore, we need a policy $\pi(a_t \vert s_t)$ that is covariant2 to translation and rotation. In other words, if the canvas is rotated or translated, the position $x$ of the atom to be placed should be rotated and translated as well.

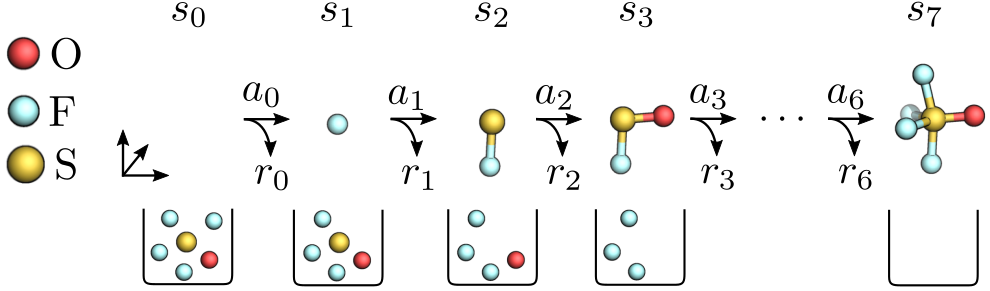

To achieve this, we first encode the current state $s_t$ into an invariant representation $s^\text{inv} = \mathsf{SchNet}(s_t)$, where $\mathsf{SchNet}$ (Schütt et al., 2017; Schütt et al., 2018) is a neural network architecture that models interactions between atoms. Given $s^\text{inv}$, our agent selects 1) a focal atom $f$ among already placed atoms that acts as a reference point, 2) an available element $e$ from the bag for the atom to be placed, and 3) the position of the atom to be placed in internal coordinates (see Figure 2). These coordinates consist of the distance $d$ to the focal atom as well as angles $\alpha$ and $\psi$ with respect to the focal atom and its neighbours. Finally, we obtain a position $x$ that features the required covariance by mapping the internal coordinates back to Cartesian coordinates. We call the resulting agent $\mathsf{Internal}$.

Figure 2: The $\mathsf{Internal}$ agent places an atom from the bag (highlighted in orange) relative to the focal atom (highlighted in purple), where the internal coordinates $(d, \alpha, \psi)$ uniquely determine its absolute position.

So… does it work?

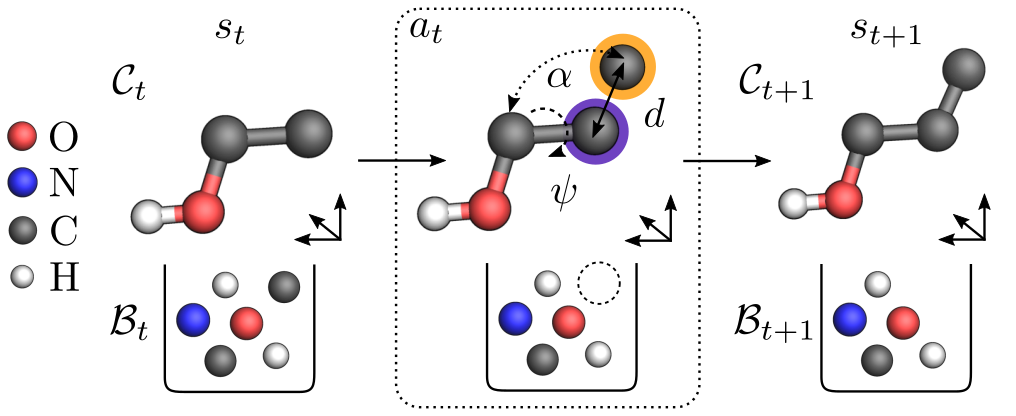

Equipped with a policy, we can finally design some molecules! To demonstrate how the $\mathsf{Internal}$ agent works, we separately train it on the bags $\ce{CH_3N_O}, \ce{CH_4O}$ and $\ce{C_2H_2O_2}$ using PPO (Schulman et al., 2017). Figure 3 shows that the agent is able to learn interatomic distances as well as the rules of chemical bonding from scratch. On average, the agent reaches $90\%$ of the optimal return3 after only $12\,000$ steps. However, from the snapshots $\enclose{circle}{2}$ and $\enclose{circle}{3}$ in Figure 3 (b) we can see that the generated structures are not quite optimal yet. While the policy has mostly learned the atomic distances, it still has to figure out the angles between atoms. After training the policy for a bit longer, at point $\enclose{circle}{4}$ we finally generate valid, stable molecules. It works!

Figure 3: (a) The $\mathsf{Internal}$ agent is able to build stable molecules from the bags $\ce{CH3NO}, \ce{CH4O}$ and $\ce{C2H2O2}$. Each dashed line denotes the optimal return for the corresponding bag. (b) Generated molecular structures at different terminal states over time show the agent's learning progress.

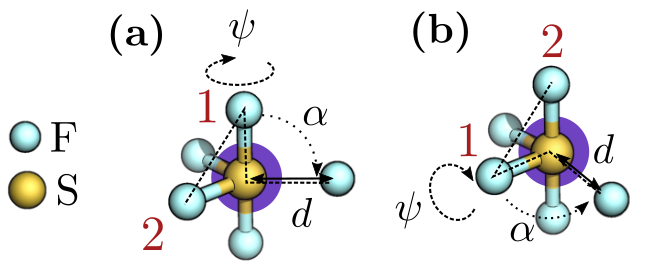

While these results look promising, the $\mathsf{Internal}$ agent actually struggles when faced with highly symmetric structures. As shown in Figure 4, that is because the choice of angles $\alpha$ and $\psi$ used in the internal coordinates can become ambiguous in such cases. A better approach would be to directly generate a rotation-covariant orientation $\tilde{x}$ of the atom to be placed without going through these internal coordinates.

Figure 4: Example of two configurations (a) and (b) that the $\mathsf{Internal}$ agent cannot distinguish. While the values for distance $d$, and angles $\alpha$ and $\psi$ are the same, choosing different reference points (in red) leads to a different action. This is particularly problematic in symmetric states, where one cannot uniquely determine these reference points.

Exploiting Symmetry using Spherical Harmonics (Simm et al., 2021)

Therefore, we replace the angles $\alpha$ and $\psi$ by directly sampling the orientation from a distribution on a sphere with radius $d$ centered at the focal atom $f$ (see Figure 5). We can define such a distribution using spherical harmonics, which are essentially basis functions defined on the sphere. In particular, we are able to model any (multi-modal) distribution on the sphere by generating the right coefficients $\hat{r}$ for these basis functions. To produce the coefficients, we modify $\mathsf{Cormorant}$ (Anderson et al., 2019), a neural network architecture for predicting properties of chemical systems that works entirely in Fourier space. Finally, we can sample a rotation-covariant orientation $\tilde{x}$ from the spherical distribution defined by $\hat{r}$ using rejection sampling. We call the resulting agent $\mathsf{Covariant}$.

Figure 5: The $\mathsf{Covariant}$ agent chooses focal atom $f$, element $e$, distance $d$, and orientation $\tilde{x}$. We then map back to global coordinates $x$ to obtain action $a_t = (e, x)$.

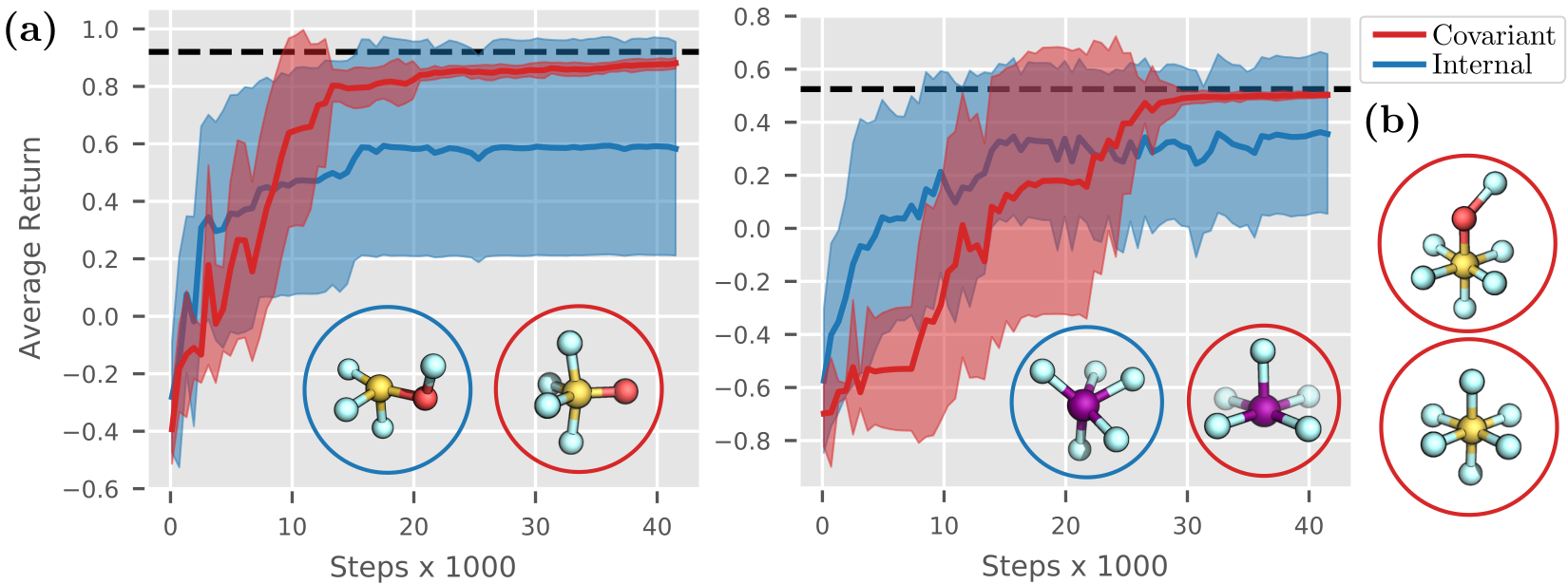

To verify that $\mathsf{Covariant}$ works as expected, we compare it to the previous $\mathsf{Internal}$ agent on structures with high symmetry and coordination numbers. As shown in Figure 6 (a), $\mathsf{Covariant}$ is able to build valid molecules from the bags $\ce{SOF_4}$ and $\ce{IF_5}$ within $30\,000$ to $40\,000$ steps, whereas $\mathsf{Internal}$ fails to build low-energy configurations as it cannot distinguish highly symmetric intermediates. Further results in Figure 6 (b) for $SOF_6$ and $SF_6$ show that $\mathsf{Covariant}$ is capable of building such structures. While the constructed molecules are small in size, recall that they would be unattainable with graph-based methods as they lack important 3D information.

Figure 6: (a) The $\mathsf{Covariant}$ agent succeeds in building stable molecules from the bags $\ce{SOF4}$ (left) and $\ce{IF5}$ (right). In contrast, $\mathsf{Internal}$ fails as it cannot distinguish highly symmetric structures. In the lower right, you can see molecular structures generated by the agents. Dashed lines denote the optimal return for each experiment. (b) Further molecular structures generated by $\mathsf{Covariant}$, namely $\ce{SOF6}$ and $\ce{SF6}$.

That’s it — a first step towards general molecular design in Cartesian coordinates

Let’s end here for now, even though we were really just getting started. To summarise, we have presented a novel reinforcement learning formulation for 3D molecular design guided by quantum chemistry. The key insight to get it to work was to exploit the symmetries of the design process, particularly using spherical harmonics.

One aspect we didn’t show today is how flexible this framework actually is. For example, we can use it to learn across multiple bags at the same time and generalise (to some extent) to unseen bags. Of course we can also scale up to larger molecules, though not quite as large as graph-based methods yet. Finally, we can even build molecular clusters, e.g. to model solvation processes. If that sounds interesting to you, make sure to check out the full papers:

- Simm et al. (2020). Reinforcement Learning for Molecular Design Guided by Quantum Mechanics. ICML 2020.

- Simm et al. (2021). Symmetry-Aware Actor-Critic for 3D Molecular Design. ICLR 2021.

-

In contrast, graph-based approaches have to resort to heuristic reward functions. ↩

-

More precisely, only the position $x$ needs to be covariant, whereas the element $e$ has to be invariant. ↩

-

We estimate the optimal return by using structural optimisation techniques to obtain the optimal structure and its energy. ↩