numbers, not adjectives — D. J. C. MacKay

9 Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Growth Rate

Carl Edward Rasmussen, February 6, 2026

Carbon Dioxide growth rate: 2.66 ± 0.28 ppm/y (mean ± 2 std dev), January 2026.

Breach of Paris Agreement +1.5°C at 450 ppm CO2 by January 2034 ± 16 months.

Release of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, or CO2, into the atmosphere is causing global warming. The underlying physical mechanism has been well understood for a long time; a quantitative account is given by S. Arrhenius in 1896: On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground; an essentially current overview is given by this report from the 1970s. More recently, attempts have been made to limit the release of greenhouse gases both nationally and globally, most prominently the Kyoto Protocol in force from 2005 and the Paris Agreement in force from 2016. In this note I assess the progress made so far in limiting atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration.

9.1 The Keeling Curve

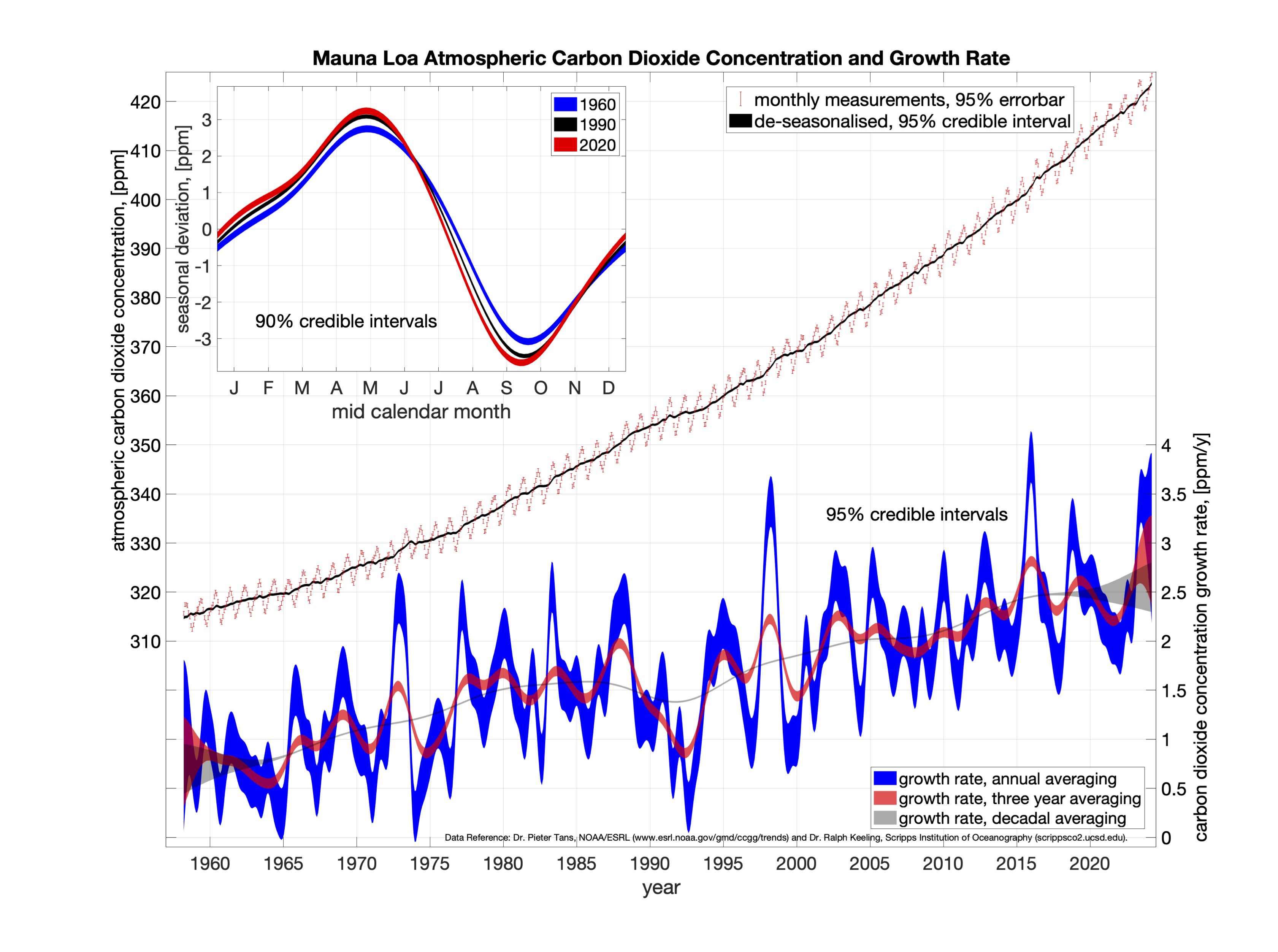

An excellent source of recent historical monthly measurements of the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide at Mauna Loa in Hawaii is available at this site, the actual data being available here. Thank you to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for providing this. The data set contains monthly average measurements from 1958 until today, shown below:

The monthly average carbon dioxide concentration in parts per million (ppm) is plotted as a function of calendar year in red in the top (left axis). This graph is sometimes known as the Keeling Curve. The data shows an increasing concentration of carbon dioxide from about 315 ppm in 1958 to about 425 ppm in 2025. For context, the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration remained constant at about 280 ppm for the 10000 years leading up to the industrial revolution. The Mauna Loa carbon dioxide concentration is not identical to the entire atmospheric average, but it’s pretty close (there is a small dependency on latitude).

The data shows a pronounced seasonal variation, which is caused by plants taking up more carbon dioxide in the summer than in winter. The inferred seasonal variation is shown for three particular years in the top left inset. The seasonal component shows a fairly rapid decrease in the four and a half months between middle of May and end of September or early October (when photosynthesis is most active in the northern hemisphere), followed by a slower rise over seven and a half months to the middle of May. The seasonal component is itself slowly changing, becoming more pronounced with time, and moving earlier in the year. The peak to peak magnitude has grown from 5.8 ppm in 1960 to 7.0 ppm in 2022. The seasonal component has a wrap-around boundary condition between December and January, and its average over a year is zero.

We are not primarily interested in seasonal fluctuations, so in the figure we have super-imposed a de-seasonalised grey region, by subtracting out the inferred seasonal variations.

What is the growth of carbon dioxide in the graph? The growth rate is the instantaneous slope of the de-seasonalised curve (also called the derivative) and is measured in parts per million per year (ppm/y). However, the raw instantaneous growth rate isn’t that useful to plot for two reasons: firstly, the instantaneous growth rate is not itself that interesting, because it doesn’t reveal much about how the carbon dioxide concentration is evolving over finite intervals of time, and secondly, the instantaneous growth rate is both very variable and associated with a large amount of statistical uncertainty, as our data only contains monthly measurements. To overcome this issue, we either 1) first compute the instantaneous growth rate and then average the result locally in time, or 2) first average the concentration values locally in time, and then compute the growth rates. In fact these two views are mathematically equivalent, so you can use whichever interpretation you prefer. The resulting growth rates are shown in the bottom (right axis).

The growth rate of the de-seasonalised carbon dioxide concentration for three different time averages, annual in blue, three-yearly in red and decadal in grey. The annual averaged growth rate tends to wobble about a fair bit. This is probably caused by random fluctuations in wind patterns leading to local effects of mixing of air volumes across altitude and latitude and to other short term variations in carbon dioxide fluxes. These effects are quite short term, typically lasting just a year or two. The annual averaged growth-rate is also associated with a fair bit of uncertainty, indicated by the width of the blue region, which corresponds to the 95% credible region. Note, that the uncertainty about decadal averaged growth rate is much smaller than the annual averaged growth rate (because it’s based on more measurements). Note also, that the band is wider towards the boundaries of the data, reflecting that we’re less certain about the rate here. In 1960-1970 the growth rate was slightly less than about 1 ppm/y, but the growth-rate has been steadily increasing, reaching 2.66±0.28 ppm/y (mean ± 2 std dev) in the middle of 2025. This means that currently, the concentration of carbon dioxide is growing by about 2.66 ppm per year.

The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) also provide a graph of carbon dioxide growth, which looks similar to the plots presented here. The difference is that the plot presented here emphasises the continuous nature of the process (rather than discrete yearly, or decade-long average growth events), and it quantifies uncertainty.

So, what does the data tell us? It shows that all is not well in the state of the atmosphere! In order to prevent further warming, the carbon dioxide levels must not grow any further. On the growth curve, this corresponds the curve having to settle down to 0 ppm/y. There is absolutely no hint in the data that this is happening. On the contrary, the rate of growth is itself growing, having now reached about 2.66 ppm/y the highest growth rate ever seen in modern times. This is not just a “business as usual” scenario, it is worse than that, we’re actually moving backward, becoming more and more unsustainable with every year. This shows unequivocally that the efforts undertaken so-far to limit green house gases such as carbon dioxide are woefully inadequate.

The deseasonalized graph is extended about a decade into the future. Note, that the further into the future predictions are made, the larger the uncertainties. The world will likely exceed the Paris Agreement limit of +1.5°C at 450 ppm, which will be reached between summer of 2032 and summer of 2035 with 95% confidence unless drastic, immediate action is taken. No evidence of such action is present in the data. Technical details.

9.2 Misleading interpretations

Unfortunately, the carbon dioxide data has been subject to some misleading interpretations, due to poor statistical reasoning. For example in the Nature Communications paper Recent pause in the growth rate of atmospheric CO2 by Keenan et al, 2016, the authors identify “a pause in the growth rate of atmospheric CO2”, lasting from 2002 to (at least) 2014. They also identify a “point of structural change” in the growth rate in 2002. In fact it is highly unlikely that any such pause or point of structural change actually exists. On the growth rate figure above, the decadal average growth rate was 1.976±0.041 ppm/y at the start of 2002 and 2.415±0.041 ppm/y at the end of 2014 (mean ± 2 std dev), so the growth rate has indeed grown. In fact, the growth rate of the growth rate (also called the acceleration) within the start of 2002 to end of 2014 interval is 0.0338 ppm/y2, exceeding the average acceleration in the 40 years prior to that (1962 to 2002) at 0.0288 ppm/y2, showing that the growth rate has in fact grown faster in the 2002 to 2014 interval, than during the 40 years prior to that. Publishing such flippant ideas should be avoided, as they create confusion where there should be clarity. It would be prudent of the authors to retract their paper (or explain why it is a valuable contribution when it doesn’t agree with observations).